The quest around building Quantum 1-Shot Signatures revolves around building practical, optimized equivocal hash functions.

Such equivocal hash functions have been proved to exist, for instance in this paper, using ordered affine partitions. Unfortunately, the proof there is essentially non-constructive, so the problem of actually building the thing™ still stands. We had a first stab at building these gadgets explicitly here, but Lev, one of the main researchers involved in this project, quickly broke the mechanism.

Now we have some other candidate constructions: Lev is working on implementing Quantum 1-shot tokens using claw-free functions — hopefully a post about this willfollow soon! — whereas Stefano and Richie are investingating an alternative approach based on ZX-calculus, which will be the focus of this post.

In general, all of these endeavours piggyback to the same problem, namely that the construction used to implement an equivocal hash function needs to be obfuscated in some way. This has a very precise meaning in cryptography, but the layman interpretation of “obfuscated” would be turn the code into a sort of black box: people can feed inputs and read outputs, but have no clue about how the program behaves. This is called black-box obfuscation, and has been unfortunately proven to be infeasible. The next best thing is called indistinguishability obfuscation — abbreviated iO — and, citing Wikipedia, it means more or less something like this:

In cryptography, indistinguishability obfuscation (abbreviated IO or iO) is a type of software obfuscation with the defining property that obfuscating any two programs that compute the same mathematical function results in programs that cannot be distinguished from each other. Informally, such obfuscation hides the implementation of a program while still allowing users to run it.

This seems rather harmless but in practice allows us to implement a ton of very well-known crypto primitives, such as public key cryptography, deniable encryption and functional encryption. So, Io has a lot of nice properties, and assuming it gives us a very nice tool for building crypto primitives in a theoretical context. Unfortunately, iO is totally impractical at the moment, so we cannot really use it to build production stuff.

So, whereas we play with indistinguishability obfuscation and other gadgets on one hand, we are also exploring more esotheric alternatives on the other hand. This basically translates into obtaining something like iO for our particular case by cutting as many corners as possible™. One of these esotheric alternatives is what this post is about. To make this explanation more palatable to the layman, from now on we’ll fix the following scenario:

Suppose that I have a pseudorandom function, which I instantiate with some random seed $r$. Suppose furthermore that I bake this thing into a (quantum) circuit. How can I rewrite the circuit so that it is difficult to “extract” $r$ by analyzing it?

You see from this how it is not unreasonable for us to believe that we can cut some corners from the full iO setting: If we pick a pseudorandom function that is difficult to invert if one doesn’t know the corresponding quantum seed, everything we need to do is making sure that the hardcoded seed cannot be easily extracted from the circuit. So, how do we make sure people won’t be able to extract $r$ by just looking at the gates of the circuit implementation?

Enter the ZX calculus

The ZX calculus is a diagrammatic calculus to express quantum circuits. The cool thing about it is that it has a bunch of very disciplined rewriting rules which can be leveraged to simplify a quantum circuit. For instance, you can take a quantum circuit, translate it into a ZX diagram, and apply the rewriting rules until you obtain a circuit that:

- Computes the same thing;

- Has some nice properties, for instance it may use a lower Toffoli gate count.

We redirect you to our previous post to know more about the ZX calculus. Everything you need to know here is that:

- Every quantum circuit can be expressed as a ZX calculus diagram;

- Every ZX calculus diagram consists of a multigraph where nodes are either decorated green dots, red dots, or yellow boxes. All these components are called spiders;

- The rewriting rules allow us to replace some tangles of spiders with others. For instance, I can merge spiders, or turn a 0-decorated spider with only 2 legs into an edge.

Pauli gadgets

In practice, this method relies on something called Pauli gadgets, which are exactly the lego bricks we need to add to our circuits to produce the noise we need and then diffuse it. To do this properly though, we need to figure out some stuff about how these gadgets commute between each other under particular conditions we are interested in. This is an open research question™ and we are exactly doing so on one hand, wereas we prepare code mocks on the other hand.

If you are interested in the technical bits, Pauli gadgets are the infinitesimal generators of the Lie algebra $\mathfrak{su}(n)$ associated to the Special unitary Lie group $SU(n)$. In the case of $\mathfrak{su}(2)$, Pauli gadgets are some of the most important single-qubit operations. In the context of the ZX calculus, Pauli gadgets admit a very particular representation. Part of our work consists in figuring out the commutation relations between higher Pauli gadgets - that is, generators of $\mathfrak{su}(n)$ for $n \geq 3$ - in purely diagrammatic terms. This will allow us to use the already developed diagrammatic-rewriting software for the ZX calculus to try this sort of obfuscation techniques.

Obfuscating circuits

Now we have all the bits to give an intuitive explanation of how our technique works. The underlying idea that we are pursuing consists in applying the ZX rewriting rules in a way which is the reverse of what people usually do: Instead of simplifying a circuit, we make it worse! In detail:

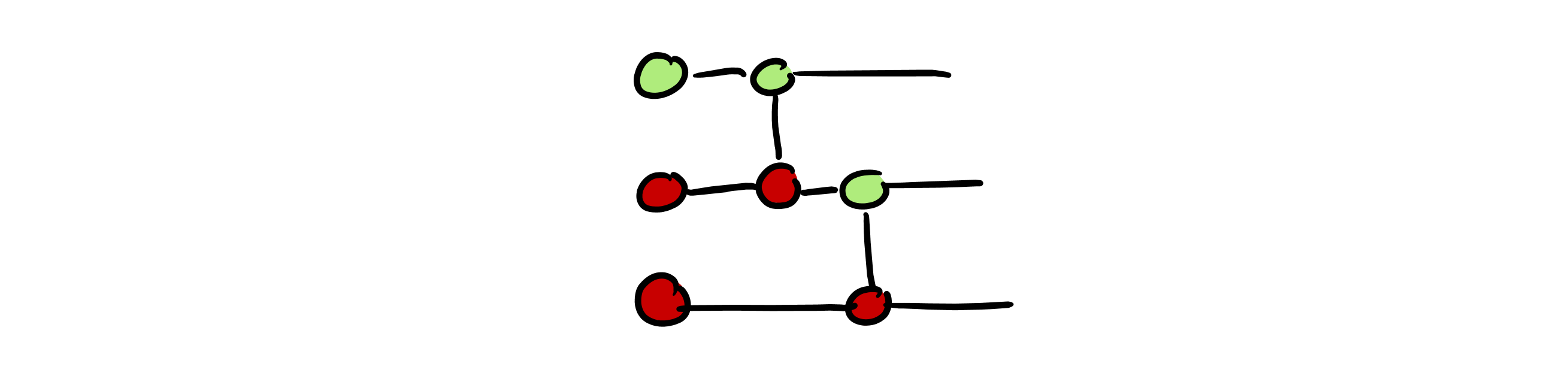

- We start with a ZX diagram representing our circuit:

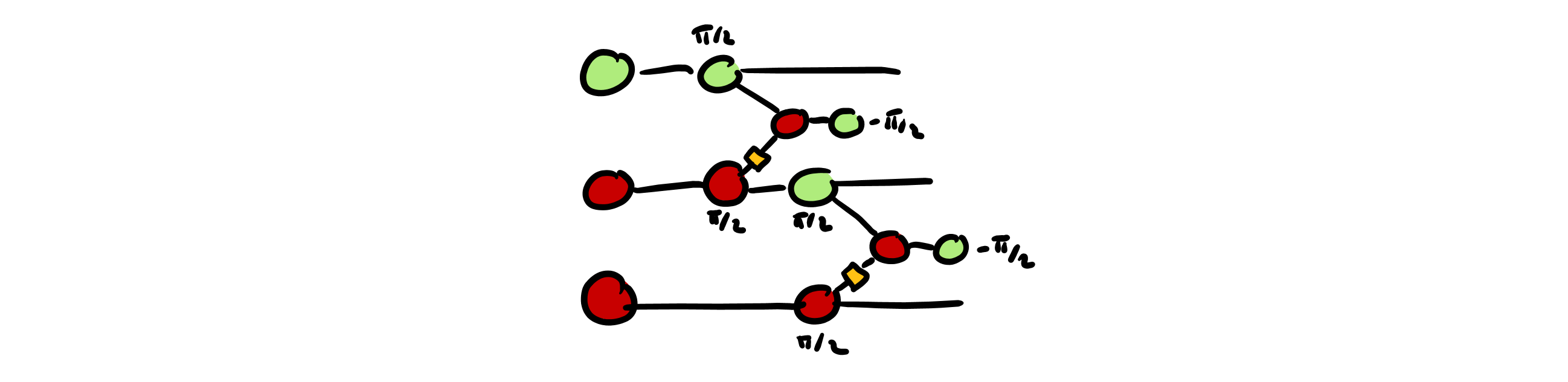

- We convert our circuit into a circuit of Pauli gadgets:

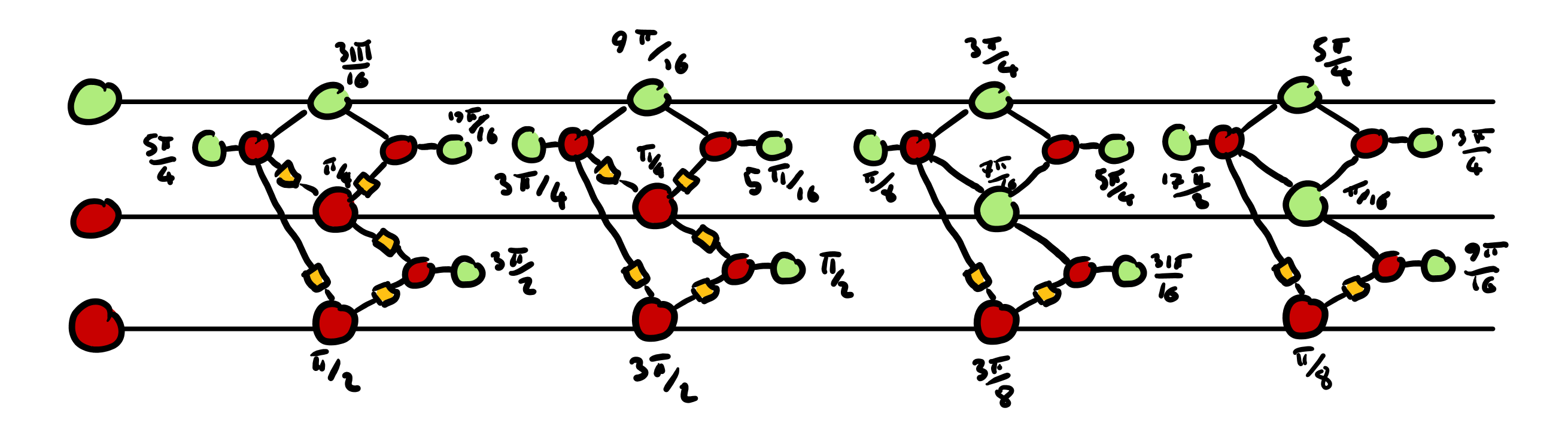

- We introduce some random Pauli gadgets into the circuit, hiding the original structure and angles. We can do this by leveraging the rules that tell us when to cancel a given spider, and applying them in reverse:

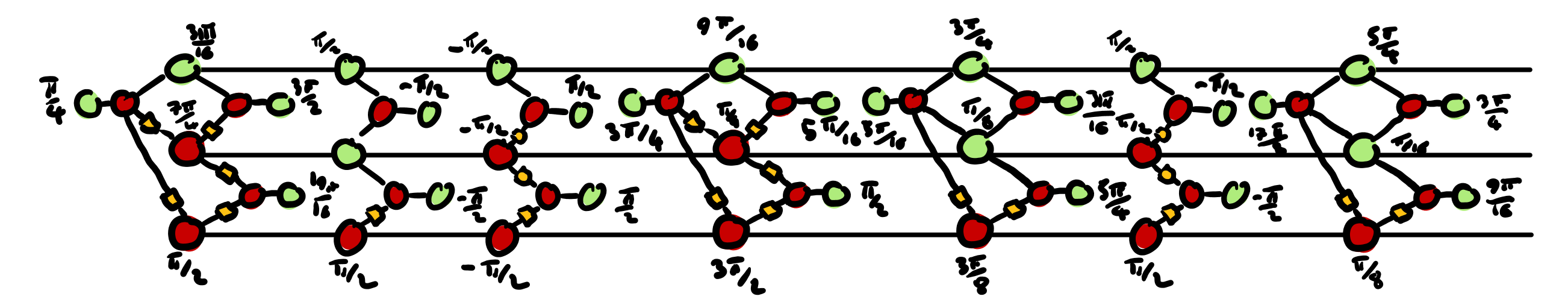

- We introduce more spiders into the circuit and we let them diffuse into the circuit, separating the Pauli gadget pairs from Step 3 and randomly permuting their angles.

The final result, shown above, is very different from the one we started with in the first picture, but these two circuits compute the same thing. In a nurshell, the technique amounts to introduce harmless noise™ — that is, noise that cancels out completely — and then letting it diffuse into the circuit in a way so that it becomes impossible to distinguish the noise from the original gates.

Since the amount of spiders we can pick to build the noise is immense, we conjecture that after the diffusion step it should be very hard to figure out how the circuit we started from looked like, that is, it’s not at all computationally easy to simplify the circuit back to its original form.

As a comparison, imagine I take a Rubik cube and scramble it randomly. If you are an inexperienced player, it will be very hard for you to figure out which moves I applied, and it will take you a long time to bruteforce your way up to the initial cube state. Similarly, in diluting the circuit with noise we let the information about the random seed $r$ of our running example dissolve into it, in a way that is not easily recoverable.

Will this work?

God knows! Obviously coming up with such an idea is easy, figuring it out in detail and implementing it is difficult, and proving that it is computationally secure is even harder. We have some proof ideas that involve random walks on a graph and some other stuff, but it’s still too early to say. Most importantly, we need to get more clarity around which complexity assumptions we would have to make so that such a proof could hold. In this respect, clearly the less the better.

Hopefully, this will be material for a future blog post. For sure, we’ll most likely publish a more detailed blog post in the upcoming weeks where the technique highlighted above is laid down in full detail; so stay tuned, and until the next time!